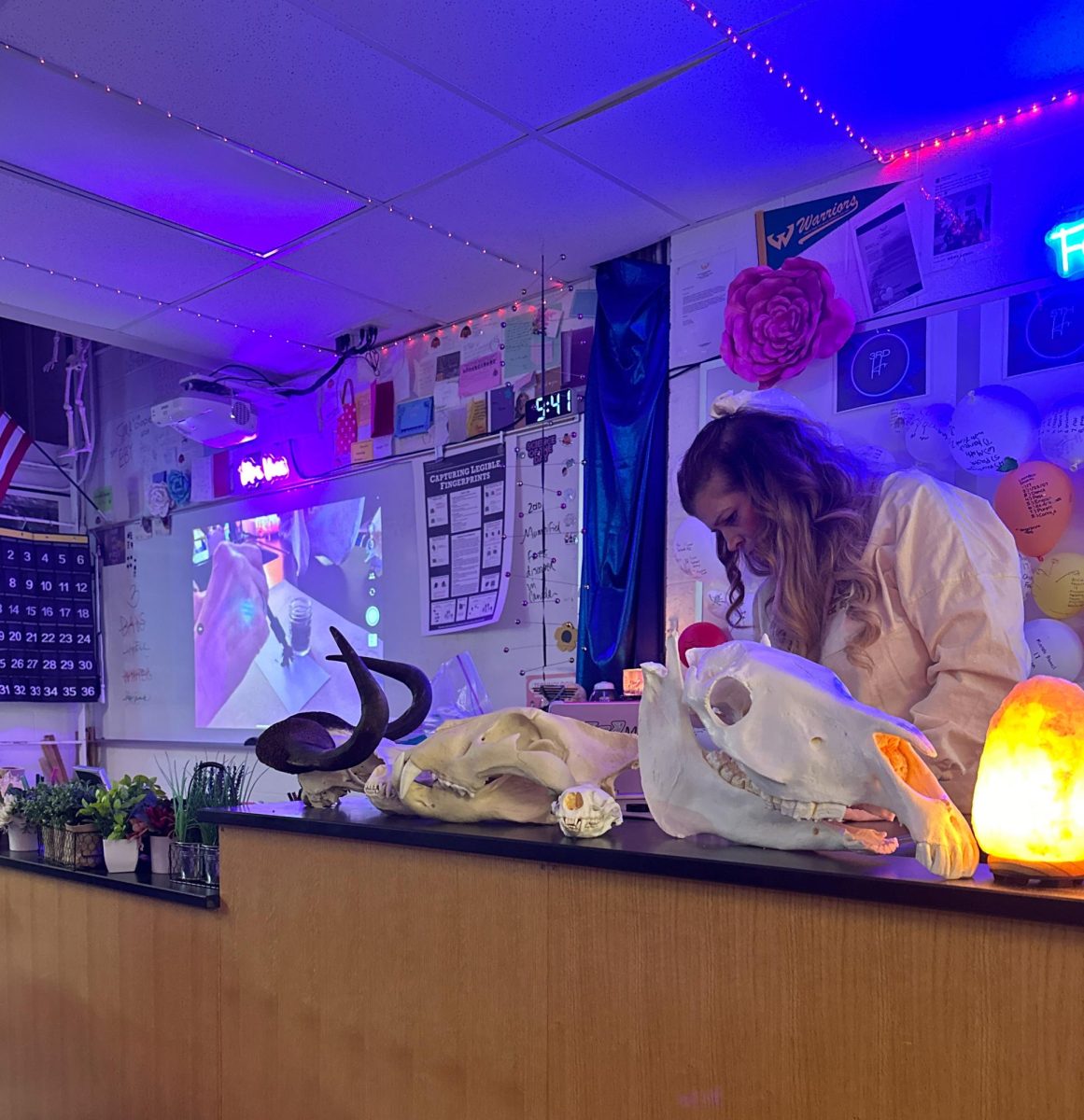

Ink-covered fingers and the five stages of human decomposition posters greet high school students as they walk into forensic science classes at P-CEP. The specialty science classrooms are decorated with crime scene tape, fake blood spatter, and outlines of human bodies on the floor.

When a forensic scientist or evidence collector enters the same room, they are searching for latent fingerprints left on the door handle, saliva left on a grande Starbucks coffee cup, and dead skin cells students leave on their desks. In order to be a forensic scientist or an evidence collector, recognizing the microscopic details the average person misses is the key to “cracking the case.”

Forensic science is a semester science class for seniors at P-CEP that teaches them the various roles of investigators and scientists who work in the forensics field. The class also gives students a surface-level understanding of the specializations in the field and how these specialists work together to solve a crime.

Due to the mature topics discussed in class, and needing a solid understanding of biology, chemistry, and physics, forensic science is reserved for the seniors at P-CEP.

“I think forensics is one of the best science classes for seniors,” says Plymouth senior and two-semester forensic science student Sydney McComb. “You’re not required to take a science class, but having a well-rounded schedule senior year is important.”

While McComb says forensic science is a “sad” class due to its morbid topics, she says, “Forensics is a really enjoyable class to learn about how things can be solved. It is a lot of communication with your peers, which I enjoy, instead of just listening to lectures like some of my science classes have been.”

Exploring diverse specializations within forensics

P-CEP students typically enjoy forensic science due to the wide range of topics covered in the class. “We touch on a lot of different sciences, but we only go two or three inches deep,” says Charles Hameline, Canton’s veteran forensic science and astronomy teacher. “We are not getting too crazy, but we talk about everything from evidence collection to serial killers and profiling, fingerprinting, blood spatter, and DNA analysis.”

Because many topics are discussed in class, it was difficult for McComb to choose a favorite unit. “So far, my favorite unit has probably been the first unit where we discussed crime scenes, because we got to look into more individual cases instead of general stuff like time of death,” says McComb. “But I am excited for second semester because I know I will enjoy the specific cases.”

The “DNA” of forensics

If not the most important piece of forensic evidence, DNA and its analysis is a crucial unit that students learn in the course.

“DNA is ridiculously important,” says Hameline. “So I think a huge takeaway from this [DNA analysis] unit is to understand what DNA is, where it comes from, and how it is relatable to other people and other organisms.”

The North Carolina Department of Justice describes DNA Analysis as, “the process of generating DNA profiles from evidence that can be compared to DNA samples from victims and other subjects involved in a case.”

DNA is unique to each person, which makes DNA that much more important to forensic scientists.

“The only person that could be genetically matched to you at that degree would be an identical twin, but that is still a very accurate match,” says Hameline.

The phrase “DNA doesn’t lie” is commonly used in the field. Suspects can find defending themselves to be difficult when their DNA is found at the scene of a crime.

Nichole Voss, a first-year forensic science teacher and veteran biology teacher at Salem says, “DNA is the gold standard from here on out. It used to be fingerprints, but now DNA has revolutionized forensics.”

Although DNA analysis is one of the most important units taught in forensic science, it is also one of the most expensive units.

“Some of those DNA labs, like gel electrophoresis, is something that is not cheap. I have $300 for class supplies for the year,” says Hameline. “So there are some labs that I have to forgo, and we have to just talk about the concepts. Unfortunately, DNA analysis is one of those units.”

Steps to specialize

Students do not necessarily have to major in forensic science during college to be a specialist. DNA analyst for the Michigan State Police Department, Kristina Ivanovic, says, “[A career in forensics is] not required to have a forensics degree, just a bachelor’s degree in the natural sciences.”

Ivanovic has a bachelor’s degree in biology and criminal justice. She enjoyed biology in high school and knew she wanted a career in the DNA field, whether forensics or in a hospital laboratory.

“I didn’t have any specific forensic science classes through my university,” says the University of Michigan-Dearborn graduate. “I knew all I wanted to do was DNA, so I chose that route of learning biology and DNA and really [honed] in on that aspect of it.”

Ivanovic’s job with the Michigan State Police is mostly a “desk job,” consisting of interpreting DNA profiles through evidence samples, determining if the samples are suitable for comparisons and if any interpretations or matches can be made.

“I also do some of the lab work,” says Ivanovic, “processing evidence samples, performing extractions on many evidence samples at once, performing quantitation on the samples, amplifying the DNA using a common process called PCR [Polymerase Chain Reaction], and separating the DNA to generate those DNA profiles that can be used for interpretation.”

First to the scene

Specialization is the key for any prospective forensic science student due its competitive nature.

“I would say because the forensic field is so broad, you should find a niche that you find to be particularly interested in and dig in that section,” says Hameline. “To say that you like forensics is great. I love that, but if you’re going to become a specialist, you have to become an expert in something specific. So I would find something that you are very interested in and just dive in.”

Although Ivanovic does not have a degree in forensic science, she started her career in a lab where she learned most of what she knows about forensics in her two years of training.

“I think [college classes] gave me a good foundation, but I learned so much more from on-the-job training, because it’s just so specific,” says Ivanovic.

Exploring a forensics career path at the high school level is often difficult due to the lack of speciality science classes.

“There are not a lot of high schools that have [forensic science],” says Voss, “so I would encourage taking advantage of being able to take the class here at P-CEP.”

Just like the career field, P-CEP’s forensic science classes are in high-demand.

Rising seniors interested in forensics can refer to P-CEP’s course catalog to learn more about the class.

“[Forensics] is a pretty sought-after class, but I would encourage it if you have an interest,” says Voss. “Sign up. I don’t think you would be sorry.”