For those who may not know, November is National Native American Heritage Month, a time to celebrate the First Nations of the Americas and their contributions to society past and present. However, November, or more accurately, the holiday of Thanksgiving, more often conjures feelings of frustration and mourning for Indigenous people in the United States.

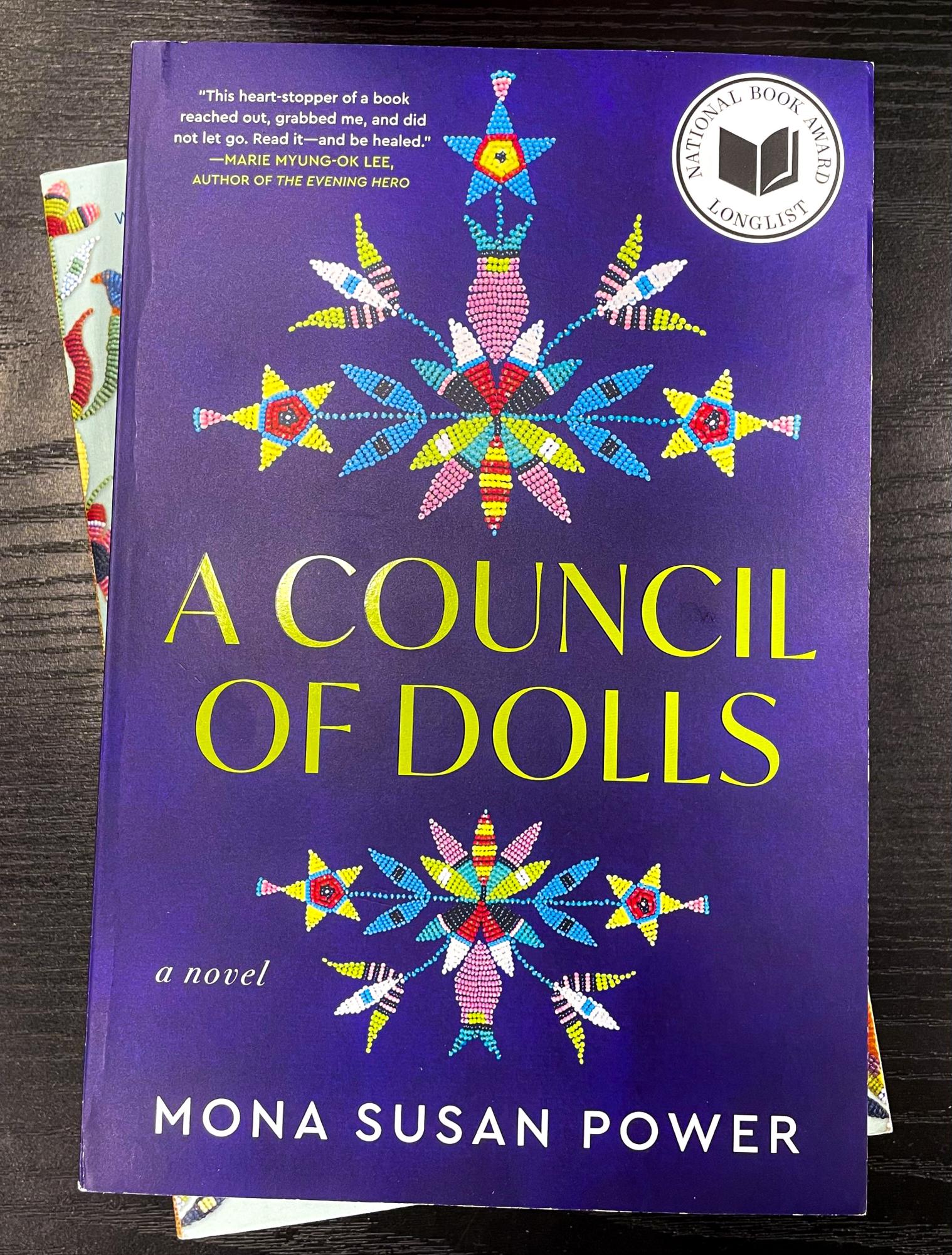

By focusing on healing from the tragedies Thanksgiving represents for Native peoples, Mona Susan Power skillfully tackles the root of generational trauma stemming from colonization in her new novel, “A Council of Dolls.” The story is a beautifully told tribute to the author’s family history, and it takes a fresh stance against the offensive “sad Indian” and “naked savage” stereotypes that have been perpetuated for the last century in popular American media.

The book is based on one of the author’s previous short stories, “Naming Ceremony,” which was published in “The Missouri Review” in 2020. Ignited by her ancestors’ experiences, Power expanded this short story into a fully-fledged novel.

The narrative takes the reader back in time, following three Yanktonai Dakhóta girls, each story told over their respective childhoods: Sissy, born in 1960s Chicago; Lillian, her mother, born in 1925 on ancestral Dakhóta land; and her mother (Sissy’s grandmother), Cora, born in 1888 and living in the aftermath of the brutal “Plains Indian Wars” away from her family at the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Boarding schools, known as residential schools in Canada, housed and “taught” more than 7,800 Native American children who were forcibly removed from hundreds of tribes across the United States, including numerous Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian villages.

The novel’s unique structure lies in the writer’s intention to help the reader understand the experiences of the girls’ mothers before her, evoking sympathy for each one. For example, the reader may have been left hating Lillian for how she approaches parenting with Sissy; thus, in the next chapter, Lillian’s childhood is laid out, giving the reader a chance to see her as the hopeful child she once was and inhibit demonization of any of the girls for their adult actions which directly stem from trauma.

As a Dakhóta woman and an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, award-winning author Mona Susan Power borrows a lot from her life and experiences for the book. Though it’s not completely autobiographical, the author herself has a lot of similarities to the first character introduced in the book, Sissy, including her birth year, her hometown, and her heritage, of course. These commonalities provide the emotional backbone of the story, making the reader feel for both the character and the author.

Sissy born last chronologically, but whose story is told first, navigates her topsy-turvy childhood under the guidance of her doll, Ethel, who seems to possess knowledge outside of Sissy’s understanding. She may not comprehend her doll’s intuitions, but Sissy, like her mother and grandmother with their respective dolls, dutifully follows her wise words.

Lillian, Sissy’s mom, is a cold, unforgiving mother, yet she tries unrelentingly to lead the best example for her daughter, even in the grip of mental turmoil.

As a child, Lillian is clingy and conflicted. She was born on the land of her ancestors but due to “civilizing” pursuits propagated by the US government, was subsequently ripped from her birthright alongside her sister, Blanche, and her doll, Mae, to be subject to cruel treatment under the control of the nuns at Bismarck Indian Boarding School in North Dakota.

Mae, a doll more sassy and less wise than Ethel, takes her name from Mae West, the black-and-white video vixen known for her husky voice and lighthearted double entendres. This reflects the doll’s nature as a fierce ally in Lillian’s childhood crises.

The most difficult story in the novel lies with Cora. As Sissy’s grandmother, she gives her kin hope for the future, but like many real-life Native Americans, Cora is reluctant to share her experiences with her family. Here, Power intelligently touches on the painful realities of many Indigenous people of the United States who are so far disconnected from their heritage and are unable to rely on their elders for assistance.

In motherhood, what Lillian lacks in warmth, Cora more than makes up for as the kind, loving maternal figure. She is the yin to her husband’s yang, who goes about recovering from his turbulent childhood through alcoholism and anger that he unleashes on Cora and Lillian.

In childhood, Cora finds herself in a difficult predicament. Her native land is unsafe, but regardless, she is removed from her tribe and taken with other young children to the cruel Carlisle Indian School. When Cora meets Jack, whose father is a white soldier, they become fast friends, together resisting the school’s aim to strip the students of their identities. Cora soon discovers, though, that her beaded deerskin doll, Winona, is more than her confidante, the soul of a murdered ancestor also possesses her.

Going through the generations, this family’s saga represents the Indigenous culture the author derives from and the journey many Native Americans take to unpack their past and that of their ancestors before them. To some, it may be labeled “magical realism,” but the events that take place in the novel are not supernatural to the characters nor the writer herself; rather, “I’m writing within my cultural system, my truth, which might not be someone else’s truth”, says Power.

In fairy-tale fashion, the novel ends on a hopeful note as Jesse, a contemporary writer in her 50s, begins to write her own story of the generations of women in her family and their dolls.

Using immersive language and a rare emphasis on complete cultural accuracy, “A Council of Dolls” flips the script on the tired stories we often hear concerning Native Americans, usually written by non-Native authors. In total contrast, Power’s writing in her newest novel weaves emotion through conflict and even manages to turn a mournful Thanksgiving into a joyous meal for Sissy where the focus is on family, food, and healing.

“A Council of Dolls” by Mona Susan Power is published by Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins. It is available in paperback, hardcover, and e-book formats, free of charge for Spotify Premium subscribers.